Shortly following the Fed meeting On January 30th, we published a summary and thoughts of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy meeting and Chairman Powell’s press conference. The market and our opinions seem to be aligned with a strong sense that the Fed was bowing to the pressure of the stock market and pivoting to a dovish tack. The following are the article’s four main takeaways:

- The Fed will be “patient” with future rate hikes, meaning they are now likely on hold as opposed to their forecasts which still call for two to three more rate hikes this year.

- The pace of QT or balance sheet reduction will not be on “autopilot” but instead driven by the current economic situation and tone of the financial markets.

- QE is a tool that will be employed when rate reductions are not enough to stimulate growth and calm jittery financial markets.

- The predominant rationale for the abrupt change in tone and possibly policy was the recent stock market weakness as well as pressure put upon the Fed by the President and the banking sector.

Having had more time to digest the statement and press conference and read other opinions, we introduce a few questions for your consideration.

What Does the Fed Know?

During the press conference, the Chairman was asked what has transpired since the last meeting on December 19, 2019, to warrant such an abrupt change in policy given that he recently stated that policy was accommodative, and the economy did not require such policy anymore. In response, Powell stated “We think our policy stance is appropriate right now. We do. We also know that our policy rate is now in the range of the committee’s estimates of neutral.” As we discussed in the original article, Powell’s response was incomplete and failed to address the question directly. Given his weak answer, we wonder if Powell knows something we don’t. Could China’s economy be rolling over at a much more concerning pace than anyone thinks? Are trade discussions with China a no-go, therefore resulting in eminent tariffs? Is a bank in trouble?

The possibilities are endless, but given Powell’s awkward response and unsatisfactory rationale to a simple and obvious question, it is possible that he is hiding something that accounts for the policy U-turn.

Has Powell Learned the Art of Politics?

The Fed is most likely aware that if a recession were to occur, their main lever for stimulating economic activity, interest rate reductions, will have little value. Given the amount of debt outstanding and the onerous burden of servicing it, the marginal benefit of lower rates will likely not provide enough benefits to lift the country out of a recession. In such a tough situation the next lever at their disposal is increasing their balance sheet and flooding the markets with liquidity via QE.

After increasing their balance fivefold during and shortly after the financial crisis, the Fed has finally begun reducing it (QT). Despite monthly reductions, currently in the $50 billion range, the balance sheet still stands at $4.05 trillion, over $3.1 trillion greater than where it stood on the eve of QE1 in 2008.

So, might Powell be taking a dovish tone to placate the markets, the President and his member banks and concurrently buying time to further normalize the balance sheet? This approach is like pouring liquid out of your cup so you can add more when the time is right. You would do this because it is not clear just how much “the cup” will ultimately hold. Bernanke and Yellen have both acknowledged that they were aware that each successive round of QE was somewhat less effective than prior rounds. That certainly must be a concern for Powell if he is called upon to re-engage QE in a recession or another economic crisis.

If this is the case, Powell will continue to publically discuss minimizing reductions to the balance sheet and refrain from further rate hikes. Despite such dovish Fed-speak, he would continue to shrink the balance sheet at the current pace. This tactic may trick investors for a few months but at some point, the market will question his intentions and damage Fed credibility.

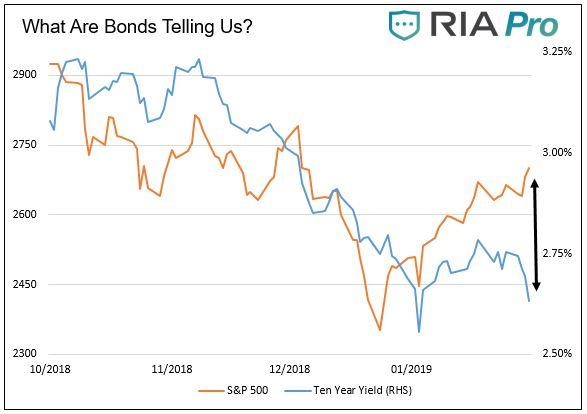

What do Bond Traders Know?

There is an old market adage that argues bond markets are usually the first to pick up on changes in the economy. As a point of context consider that in June of 2007, ten year U.S. Treasury yields peaked at 5.25%. By the time the S&P 500 peaked five months later, ten-year yields had fallen nearly 1%. By the time the S&P was down 20% from most recent highs, ten-year yields had fallen to 3.50%. Clearly, in that time, the bond market was onto something well before the stock market.

On Wednesday, after the Fed’s statement and press conference, ten -year yields stood at 2.677% down from 2.740% before the announcement. In mid-November, 10-year yields were 3.206%. In the 10-weeks leading up to the formal reversal of Fed policy from tightening to pause, rates fell 53 basis points (0.53%). The Fed’s dovish tone is inflationary on the margin. Accordingly, bond markets should be concerned and yields should be higher especially the longer-dated bonds like 10s and 30s. They are not. What do bond traders know that the rest of us don’t?

Summary

The Fed has a long history of using economic jargon and, quite frankly, non-truths to help promote their agenda. The point of this piece is to assume that Powell is cut from the same cloth as his predecessors so we can understand what might be transpiring before it is generally known by the investing public. This knowledge puts us in a much better position to manage our investment and risk postures.

Michael Lebowitz, CFA is an Investment Analyst and Portfolio Manager for RIA Advisors. specializing in macroeconomic research, valuations, asset allocation, and risk management. RIA Contributing Editor and Research Director. CFA is an Investment Analyst and Portfolio Manager; Co-founder of 720 Global Research.

Follow Michael on Twitter or go to 720global.com for more research and analysis.

Customer Relationship Summary (Form CRS)